Click on the image to watch the video

Delft Robotics Institute: robots for people and with people.

I was happy to hear and see that the myth of robots taking over the world is finally also among roboticists being replaced by the best cooperation between humans and robots.

In my TEDx-Delft-presentation you can see what I had to say about these themes:

SCIENCE JOURNALIST - WRITER - SPEAKER @ ClearScience42 ***** Specialized in artificial intelligence, robots, the brain and Alan Turing***Gespecialiseerd in kunstmatige intelligentie, robots, het brein en Alan Turing.

Friday, January 25, 2013

Sunday, January 6, 2013

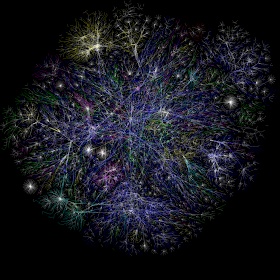

The Internet turns 30 - Happy birthday!

A brief history of the Internet

1969 The first version of the ARPANET, developed by the United States Department of Defense. The ARPANET is the predecessor of our present day Internet.

1971 Ray Tomlinson sends the world's first e-mail between two computers of the ARPANET. He is the first to use the @-sign in an e-mail address.

1983 DARPA (America's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) adopts the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) as the standard protocol for communication between computers. The Internet is born on January 1, 1983. It consists of a network of 500 computers at universities and US government institutions.

1990 Birth of the World Wide Web at the CERN-institute in Geneva (Switzerland). The whole world should thank Tim Berners-Lee that his invention was not patented and commercialized, but stayed an open, free infrastructure. Wouldn't he deserve the Nobel Peace Prize for this?

Note: Many people confuse the Internet with the World Wide Web. They are not the same. The Internet is the infrastructure underlying the World Wide Web, like motorways are the underlying structure for cars, motorcycles and trucks. The Internet is a network of computer networks. WWW is one of the services that runs on the Internet, but there are more services, such as e-mail, FTP, VoIP and Usenet.

1991 Info.cern.ch is the first website, running on a NeXT-computer at CERN

1992 Website-registration for the Internet begins with domain names ending on .com, .net, .org, .gov and .edu.

1993 CERN opens up the World Wide Web for everyone.

1994 Release of the Netscape Navigator, a browser for the Internet. Creation of JAVA.

1995 Foundation of Yahoo, Amazon.com and eBay.

1996 Launch of Hotmail

1997 The Amsterdam Internet Exchange is launched. Amsterdam becomes the Internet capital of the world.

1998 Google founded

2000 Burst of Dot.com-bubble

2001 Launch of Wikipedia

2003 Launch of Second Life

2004 Launch of Facebook

2005 Launch of YouTube and Google Earth

2006 Launch of Twitter

2006 Web Science becomes the scientific study of the Web

2011 Although it is really too much honor to call the Arab Spring a Facebook- or a Twitter-revolution, Facebook and Twitter definitely play an accelerating role in spreading the revolutionary spirit during the Arab Spring.

2013 Internet @30...More than 2,4 billion people worldwide use the Internet. If the Internet were a country, it would rank as the world's fifth-largest economy.

To-Do-list for the next 30 years:

- One-third of the world population has now access to Internet. But that also means that two-third of the world population has no access. The next challenge is to connect all world citizens.

- Our present Internet connects computers and people. The next step will be to also connect THINGS: your car, your fridge, your house. As more and more things are getting sensors and chips, they can be connected to the Internet

- Turning the Internet in a true and beneficial Social Machine that uses Big Data. Read my interview with Dame Wendy Hall about the Social Machine.

- Interplanetary Internet

More about the Internet on the Internet:

Read here more about the history of the Internet.

Visit also the The Big Internet Museum

Internet World Stats collects statistics about the use of Internet in the world

Wednesday, January 2, 2013

Videozoekmachine wordt volwassen

Een steeds groter deel van de gedigitaliseerde informatie bestaat uit beeld: van vakantiefoto’s op Facebook, homevideo’s op YouTube tot professionele filmreportages in beeldarchieven. Wat zou het handig zijn als we in die beelden net zo goed en snel zouden kunnen zoeken als zoekmachines kunnen in tekst. Zoek je filmbeelden van wielrenners die voor de camera ontkennen dat ze ooit doping hebben gebruikt, dan zou je de de bijbehorende filmfragmenten met slechts een paar trefwoorden willen vinden: bijvoorbeeld ‘wielrenners’, ‘doping’ en ‘ontkenning’ of liever nog met een grammaticaal correcte opdracht als ‘Geef me alle filmfragmenten van wielrenners die voor de camera ontkennen dat ze ooit doping hebben gebruikt’.

Dat lijkt veel eenvoudiger dan het is. In werkelijkheid is automatische beelddetectie een van de grootste uitdagingen in de informatica. Neem bijvoorbeeld het filmbeeld van een man die een overval pleegt op een slijterij. Het herkennen van individuele voorwerpen zoals ‘man’, ‘fles’ en ‘toonbank’ lukt een computer al vrij aardig, maar het begrijpen en onder woorden brengen van de relatie tussen alle individuele voorwerpen in een samengesteld beeld − in dit geval: ‘een man pleegt een overval op een slijterij’ − is voorlopig nog een brug te ver. Toch is er in de afgelopen tien jaar veel vooruitgang geboekt. En daaraan heeft informaticus Cees Snoek van de Universiteit van Amsterdam (UvA) een stevige bijdrage geleverd.

Doorbraak in beeldzoeken “Tot eind jaren negentig probeerden wetenschappers computers beelden te laten begrijpen door modellen van voorwerpen te bouwen”, zegt Snoek. “Zo’n model vertelt de computer bijvoorbeeld dat ‘een stoel vier poten heeft’ en dat ‘een zeilboot een grote romp en een zeil heeft en omringd wordt door blauw water’. Voor elk voorwerp had de computer een apart algoritme nodig. Dat heeft niet tot de gehoopte doorbraak in videozoeken geleid.”

Die doorbraak kwam pas met een model dat de Amerikaan David Lowe in 1999 ontwikkelde. Dit model is geïnspireerd op de manier waarop het menselijk brein visuele informatie begrijpt. Snoek: “Kort gezegd maakt het model een zo compact mogelijke beschrijving van de nabije omgeving van elk pixel. Hoe verandert in de omliggende pixels het contrast, de textuur en de beweging? Die beschrijving filtert alle toevalligheden, zoals de opnamehoek of de schaduw, eruit. Zo ontwikkelde Lowe een algoritme dat alle mogelijke concepten aan kan. In het werk van Lowe zat nog geen kleurinformatie. Dat hebben wij er aan toegevoegd en die uitbreiding gebruikt nu ook de hele wereld in ons vakgebied. Een tweede belangrijke bijdrage aan de geboekte vooruitgang was het beschikbaar komen van heel veel beelddata en het vermogen van algortimen om steeds beter te leren van al die voorbeelden.”

Snoek is de onderzoeksleider van de MediaMill Semantic Video Search Engine, een videozoekmachine van de UvA die jaarlijks hoge ogen gooit in een internationale wedstrijd voor videozoekmachines, georganiseerd door het Amerikaanse National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). In 2008, 2009 en 2010 won de UvA-zoekmachine de wedstrijd. “Dat laat zien dat ons onderzoek op wereldniveau zit,” zegt Snoek, “en dat heeft er ongetwijfeld toe bijgedragen dat ik nu de Nederlandse prijs voor ICT-onderzoek heb gewonnen.”

Het verhaal achter het beeld

Snoek probeert niet alleen de huidige versie van de MediaMill Semantic Video Search Engine beter, sneller en robuuster te maken, hij wil ook nieuwe wegen inslaan. Een van die wegen moet het handmatig labelen van beelden automatiseren. Nu nog labelen onderzoekers de trainingset met beelden handmatig. Om boten te herkennen geven ze de computer een heleboel voorbeelden van boten, waaraan ze zelf het label ‘boot’ hebben gehangen. Snoek: “Dat handwerk wil ik vervangen door het verzamelen van gelabelde beelden van het internet. Dan loop je in eerste instantie tegen het probleem op dat veel labels helemaal niet hoeven te kloppen met het beeld. Een foto van een boot kan bijvoorbeeld het label ‘vakantie’ dragen. Maar we hebben inmiddels een algoritme ontwikkeld dat dit probleem op een effectieve manier oplost.”

Een tweede nieuwe weg die Snoek wil in slaan, is het interpreteren van een beeld in een gehele zin in plaats van alleen in een enkel concept, zoals nu nog gebeurt. “Neem een beeld waarop een vrouw en een fiets te zien zijn. De computer zou dan moeten herkennen of de vrouw langs de fiets loopt, of op de fiets rijdt, of misschien wel de fiets aan het stelen is. De computer moet dan niet alleen met zelfstandige naamwoorden op de proppen komen, maar ook met werkwoorden en voorzetsels. Het ultieme doel is dat een computer de beeldscène omschrijft in een verhaal, zoals mensen dat ook kunnen.”

De beeldzoektechnieken die Snoek met zijn collega’s ontwikkelen, worden sinds kort ook in de praktijk toegepast. Het Nederlands Instituut voor Beeld en Geluid in Hilversum gebruikt de technieken om meer dan 750.000 uur aan videomateriaal doorzoekbaar te maken. En het Nederlands Forensisch Instituut is geïnteresseerd in het toepassen van de techniek om bijvoorbeeld grote hoeveelheden in beslag genomen videomateriaal te filteren op de aanwezigheid van kinderporno.

Het prijzengeld van € 50.000 dat verbonden is aan het winnen van de Nederlandse Prijs voor ICT-onderzoek is voor Snoek een welkome steun in de rug. “Een deel ervan wil ik gebruiken om buitenlandse onderzoekers van naam en faam naar Nederland te halen voor het geven van lezingen. Met een ander deel wil ik mijn promovendi ondersteunen bij de aanschaf van bijvoorbeeld een nieuwe computer of andere hardware. Verder wil ik ook een deel van het geld besteden om een samenwerking met China op te zetten. Een voormalige student van mij is nu universitair docent in Peking en dat contact kan ik gebruiken om de samenwerking met China uit te breiden.”

Internet

http://www.ceessnoek.info/

Kort CV Cees Snoek:

Cees Snoek (1978) studeerde business information systems aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam (UvA, 2000) en promoveerde aan dezelfde universiteit in de informatica (2005). Momenteel is hij universitair docent bij het Instituut voor Infomatica van de UvA en hoofd R&D van het spin-offbedrijf Euvision Technologies. Snoek is gespecialiseerd in automatische zoektechnieken voor video. Hij is de onderzoeksleider van de MediaMill Semantic Video Search Engine, een videozoekmachine die driemaal als ’s werelds beste uit de bus kwam. In de afgelopen jaren won Snoek diverse onderzoeksbeurzen: NWO Veni (2008), Fulbright Junior Scholarship (2010) en een NWO Vidi-beurs (2012). Op 30 oktober 2012 ontving hij de Nederlandse Prijs voor ICT-onderzoek (voor onderzoekers onder de veertig jaar). Het prijzengeld van € 50.000 mag hij vrij besteden aan ICT-onderzoek. De prijs is ingesteld door het ICT-onderzoek Platform Nederland (IPN) en NWO Exacte Wetenschappen, met steun van de Koninklijke Hollandsche Maatschappij der Wetenschappen (KHMW).

Cees Snoek (1978) studeerde business information systems aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam (UvA, 2000) en promoveerde aan dezelfde universiteit in de informatica (2005). Momenteel is hij universitair docent bij het Instituut voor Infomatica van de UvA en hoofd R&D van het spin-offbedrijf Euvision Technologies. Snoek is gespecialiseerd in automatische zoektechnieken voor video. Hij is de onderzoeksleider van de MediaMill Semantic Video Search Engine, een videozoekmachine die driemaal als ’s werelds beste uit de bus kwam. In de afgelopen jaren won Snoek diverse onderzoeksbeurzen: NWO Veni (2008), Fulbright Junior Scholarship (2010) en een NWO Vidi-beurs (2012). Op 30 oktober 2012 ontving hij de Nederlandse Prijs voor ICT-onderzoek (voor onderzoekers onder de veertig jaar). Het prijzengeld van € 50.000 mag hij vrij besteden aan ICT-onderzoek. De prijs is ingesteld door het ICT-onderzoek Platform Nederland (IPN) en NWO Exacte Wetenschappen, met steun van de Koninklijke Hollandsche Maatschappij der Wetenschappen (KHMW).

Creating social machines for the greater good

The Internet has evolved from a read-only Web, via a read/write Web to a social Web in which humans are becoming part of the machine. Dame Wendy Hall, Professor of Computer Science at the University of Southampton, has always been at the forefront of the science that has led to social machines.

This article has been published in I/O Magazine, december 2012

Dame Wendy Hall is an atypical computer scientist. She doesn’t like programming. She doesn’t like geek speak. She likes dealing with people. ‘I am a people person, whereas an awful lot of computer scientists don’t like dealing with people,’ she says after having delivered her lecture Web Science: The Theory and Practice of Social Machines at ICT.OPEN 2012 in Rotterdam last October.

Web science is a perfect example of the unique interplay between the scientific and the engineering components of computer science: an interplay between fundamental scientific developments and the practical tool created by computer scientists: the Web. And the social machine is to web scientists what the telescope is to astronomers. ‘Social machines collectively use the power of the human brain, together with the power of machines, for the greater good,’ says Hall, adding, ‘although of course there will also be a greater bad.’

As Hall sees it, the main question that social machines can help us answer is how certain phenomena emerge on the Web. ‘A well-known example involves Twitter, a social machine that we use a lot in our scientific research in Southampton. Who influences whom on Twitter? Who are the creative thinkers? Who are the followers? Who amplifies messages? These are interesting questions to answer. Let me give another example of what a social machine can do in the medical domain. In a small country, only a few people might suffer from some rare disease. But on a global scale that can add up to a significant number of people. A social machine can help patients and their families share their knowledge and experiences.’

Explorers

With the others in her research group at the University of Southampton, Hall is working to characterise and classify social machines, but also to build social machines of their own. She aims to develop a Web observatory where people all over the world can share the data they are gathering about the Web. Hall: ‘Astronomers are already sharing data gathered from different places around the world to create more powerful telescopes. Ideally there should be Web observatories all over the world, including the one we are building at Southampton, coordinated through the Web Science Trust, which is hosted at Southampton.

In considering the potential of social machines, we have to remember, Hall says, that we are still in the very early days. ‘We are explorers in new terrain. It’s like with the computer in the 1940s. People still had to discover what computers are and what computer science is. More social machines fail than succeed. But looking at the failures is as important as looking at the successes. Actually, the Web itself is only so young and therefore still fragile. Governments and companies often don’t understand the digital ecosystem. Companies are afraid to be open and some even try to challenge the principle of net neutrality. Sometimes I feel that just as we could destroy the physical ecosystem on the planet, we could also destroy the digital ecosystem.’

In Hall’s view, humans are an essential part of the social machine: ‘Social machines are not Turing machines anymore. The social machine can be seen as Turing machines in combination with the unpredictable ‘us’. The Web is a sociotechnical system. Social machines are redefining what machines are. They are changing us. But how? The jury is still out. We need data, lots of data. The medical world could profit a lot from health data. We need to get health data out, whilst still ensuring privacy.’

Keeping a close eye on both the element of privacy and the terms under which data can be used is an important issue when it comes to collecting data. Another important issue is that many companies are reluctant to share the data they ‘own’. ‘But in the end,’ says Hall, ‘it’s all about return on investment. If the return is higher than the investment, then it’s worth sharing data.’

Role model Now 60, Hall flies all over the world to give talks about web science and the potential of social machines. ‘I feel privileged that I am ending my scientific career on a real high. All that I have done before is coming together in what I am doing now.’ In 2012, Computer Weekly ranked her second among the ‘most influential women in UK IT’. Hall is seen as a role model for women in science. ‘I have accepted that role, although I have never had kids. I’ve never had to combine family with work and in that sense I am not a role model.’

Throughout her career, Hall has tried to involve more women in computer science. But sometimes she gets tired of the gender issue. ‘Then I think: this is just the way it is. Yes, we do need more women in programming, in building computer architectures, in senior positions, but the pipeline is so empty. Unfortunately it’s almost as if we have lost the battle in computer science. We have created this culture that women just don’t enjoy. On the other hand, women do enjoy talking about the social implications of computer science. My research group counts far more women than the average research group in computer science. That’s because our research is close to the social sciences and the humanities where there are more women than men. I have no problem involving more women in web science and that makes me happy.’

Although Hall likes to study and construct social machines, she is a late adopter herself. ‘I use Twitter, but only since 2009. I enjoy Twitter because it’s a good way to communicate with a large number of people. But I don’t use Facebook. I just don’t want to take the time for it. For me, computer science has always been about how people use computers. I have never been interested in writing programs or compilers. Honestly speaking, computers really annoy me. If I ever have problems with my computer or with the network, I give them to the technical support team to fix.’

Short CV:

Wendy Hall was born in London in 1952. She received a bachelor’s degree and a PhD in mathematics from the University of Southampton. In 1984 she became a computer science lecturer at the same university. She did pioneering research in the field of multimedia and was the co-inventor of the Microcosm hypermedia system, a predecessor of the World Wide Web that ran on a closed network of computers. In 1994 she was appointed Professor of Computer Science at the University of Southampton. In 2006 she co-founded the Web Science Research Initiative (together with, among others, Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web). From 2008 to 2010 she was President of the ACM (Association for Computing Machinery). In 2009 she was awarded the title Dame Commander of the British Empire and she was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society. From 2008-2011 she was a guest professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing. Wendy Hall is married and has no children.

Web science is a perfect example of the unique interplay between the scientific and the engineering components of computer science: an interplay between fundamental scientific developments and the practical tool created by computer scientists: the Web. And the social machine is to web scientists what the telescope is to astronomers. ‘Social machines collectively use the power of the human brain, together with the power of machines, for the greater good,’ says Hall, adding, ‘although of course there will also be a greater bad.’

As Hall sees it, the main question that social machines can help us answer is how certain phenomena emerge on the Web. ‘A well-known example involves Twitter, a social machine that we use a lot in our scientific research in Southampton. Who influences whom on Twitter? Who are the creative thinkers? Who are the followers? Who amplifies messages? These are interesting questions to answer. Let me give another example of what a social machine can do in the medical domain. In a small country, only a few people might suffer from some rare disease. But on a global scale that can add up to a significant number of people. A social machine can help patients and their families share their knowledge and experiences.’

Explorers

With the others in her research group at the University of Southampton, Hall is working to characterise and classify social machines, but also to build social machines of their own. She aims to develop a Web observatory where people all over the world can share the data they are gathering about the Web. Hall: ‘Astronomers are already sharing data gathered from different places around the world to create more powerful telescopes. Ideally there should be Web observatories all over the world, including the one we are building at Southampton, coordinated through the Web Science Trust, which is hosted at Southampton.

In considering the potential of social machines, we have to remember, Hall says, that we are still in the very early days. ‘We are explorers in new terrain. It’s like with the computer in the 1940s. People still had to discover what computers are and what computer science is. More social machines fail than succeed. But looking at the failures is as important as looking at the successes. Actually, the Web itself is only so young and therefore still fragile. Governments and companies often don’t understand the digital ecosystem. Companies are afraid to be open and some even try to challenge the principle of net neutrality. Sometimes I feel that just as we could destroy the physical ecosystem on the planet, we could also destroy the digital ecosystem.’

In Hall’s view, humans are an essential part of the social machine: ‘Social machines are not Turing machines anymore. The social machine can be seen as Turing machines in combination with the unpredictable ‘us’. The Web is a sociotechnical system. Social machines are redefining what machines are. They are changing us. But how? The jury is still out. We need data, lots of data. The medical world could profit a lot from health data. We need to get health data out, whilst still ensuring privacy.’

Keeping a close eye on both the element of privacy and the terms under which data can be used is an important issue when it comes to collecting data. Another important issue is that many companies are reluctant to share the data they ‘own’. ‘But in the end,’ says Hall, ‘it’s all about return on investment. If the return is higher than the investment, then it’s worth sharing data.’

Role model Now 60, Hall flies all over the world to give talks about web science and the potential of social machines. ‘I feel privileged that I am ending my scientific career on a real high. All that I have done before is coming together in what I am doing now.’ In 2012, Computer Weekly ranked her second among the ‘most influential women in UK IT’. Hall is seen as a role model for women in science. ‘I have accepted that role, although I have never had kids. I’ve never had to combine family with work and in that sense I am not a role model.’

Throughout her career, Hall has tried to involve more women in computer science. But sometimes she gets tired of the gender issue. ‘Then I think: this is just the way it is. Yes, we do need more women in programming, in building computer architectures, in senior positions, but the pipeline is so empty. Unfortunately it’s almost as if we have lost the battle in computer science. We have created this culture that women just don’t enjoy. On the other hand, women do enjoy talking about the social implications of computer science. My research group counts far more women than the average research group in computer science. That’s because our research is close to the social sciences and the humanities where there are more women than men. I have no problem involving more women in web science and that makes me happy.’

Although Hall likes to study and construct social machines, she is a late adopter herself. ‘I use Twitter, but only since 2009. I enjoy Twitter because it’s a good way to communicate with a large number of people. But I don’t use Facebook. I just don’t want to take the time for it. For me, computer science has always been about how people use computers. I have never been interested in writing programs or compilers. Honestly speaking, computers really annoy me. If I ever have problems with my computer or with the network, I give them to the technical support team to fix.’

Short CV:

Wendy Hall was born in London in 1952. She received a bachelor’s degree and a PhD in mathematics from the University of Southampton. In 1984 she became a computer science lecturer at the same university. She did pioneering research in the field of multimedia and was the co-inventor of the Microcosm hypermedia system, a predecessor of the World Wide Web that ran on a closed network of computers. In 1994 she was appointed Professor of Computer Science at the University of Southampton. In 2006 she co-founded the Web Science Research Initiative (together with, among others, Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web). From 2008 to 2010 she was President of the ACM (Association for Computing Machinery). In 2009 she was awarded the title Dame Commander of the British Empire and she was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society. From 2008-2011 she was a guest professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing. Wendy Hall is married and has no children.